“Social attraction.” It’s not exactly a new idea.

Human hunters have used decoys and calls to attract prey forever. And biologists have used recorded bird sounds to try to attract and repel birds for a long time. (We did it back when I was a lad, and I assure you that “portable” tape recorders were just barely portable back then!)

Birds are social animals. Different species enjoy different social lives, some want to avoid competitors, some want to attract mates (and repel competitors), and some like crowds, especially for nesting.

For the gregarious nesters, this means that, like people, they are attracted to places that are crowded, full of the sight and sounds of other birds. This preference has a perverse side: a perfectly good nesting area with no inhabitants may be overlooked. This matters for conservation projects that protect nesting areas. If they are too empty, the intended beneficiaries will ignore them, and miss out.

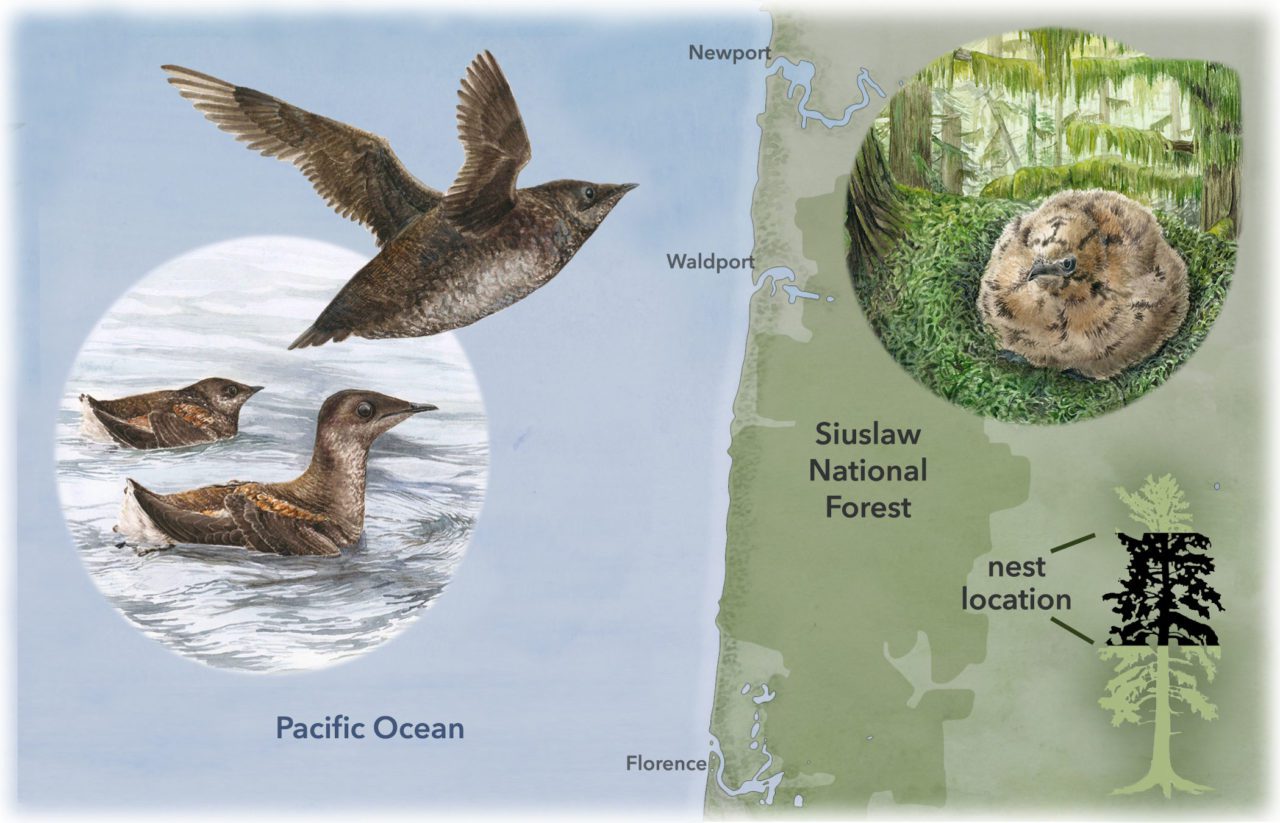

This spring, Carrie Arnold reports on efforts in Oregon to attract Marbled Murrelets to safe nesting areas in the forests using species appropriate “social attraction” [1]. These sea birds are pretty darned picky. They live and feed on the ocean, but nest inland, in “Methuselah-like trees with wide, flat limbs that are close to the coast, but not too close; accessible, but concealed.” They don’t build nests, they scoop out a comfy spot in the mossy limb, high up in the trees. Parents commute out to sea to bring back sea food, swooping in and out at 100 kph.

After decades of incredibly patient observation of these birds, researchers moved to try to attract Marbled Murrelets to safe, unused nesting areas. In this case, the birds are nearly invisible to each other as well as to ornithologists. So, visual decoys aren’t relevant. But they birds can hear the cries of other nesting pairs. So the project introduced sound systems that emit recorded breeding calls. This did, indeed, attract breeding pairs, and more than a dozen chicks lived to fly out to sea.

Arnold notes that this effort in Oregon joins dozens of other similar programs around the world. (And, as the Cornell editors note in a sidebar, “Many Social-Attraction Projects Use Macaulay Library Audio”.) It’s not enough to just protect habitat, it may be necessary to “market” it to the intended customers. : – )

Unfortunately, these picky nesters are still in a lot of trouble. They feed out in the Pacific, harvesting the rich bounty of the northern Pacific upwelling. These areas have been devastated by more extreme and more frequent marine heat waves, and, as Arnold puts it, “Oregon’s murrelets can’t take too much more of that.”

- Carrie Arnold, Sounds Like Home: Experimenting with Audio to Help Marbled Murrelets Find Prime Habitat, in All About Birds, April 4, 2022. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/sounds-like-home-using-audio-to-help-marbled-murrelets-find-nest-sites/