We’ve all been concerned about the rapid melting of all the ice in Greenland, and the rapid thinning of the Arctic ice sheet. When—not if—these areas melt completely, it will raise mean sea level a bit. Knee deep, or maybe waist deep. Significant, but survivable.

And we’ve been watching West Antarctica, which seems to be melting faster these days. If West Antarctica eventually melts completely, that would be another 3+ meters of sea level. Over your head. Up to the second story. Glub. Pretty bad for coastal areas.

Until recently, East Antarctica has seemed stable. This is the big one, with 4/5 of the worlds ice. If West Antarctica were to melt down, that would mean a rise of 50 meters, up to the 10 floor, in mean sea level. Pretty much game over for human civilization.

This spring Alec Luhn discusses recent signs of instability in East Antarctica, which are, *ahem*, concerning to say the least [1].

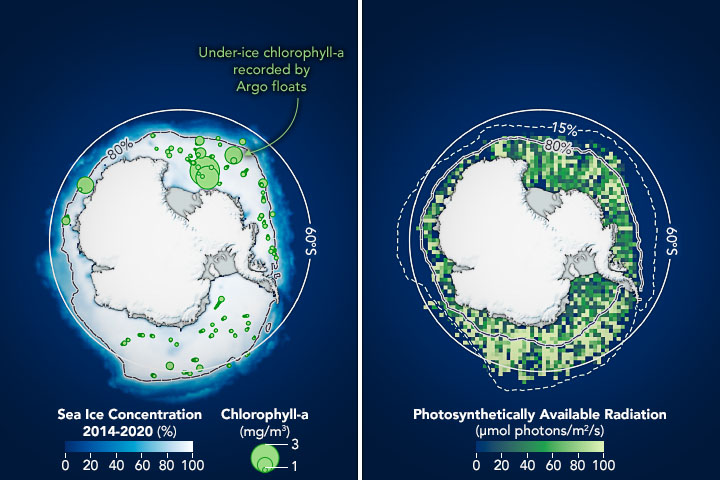

In part, the new concerns reflect an increase in available data. This area is extremely difficult to access, so there has been very little information about the ice, underlying rock, and the important coast lines under the sea ice. All the theoretical models in the world tell us nothing in the absence of adequate data.

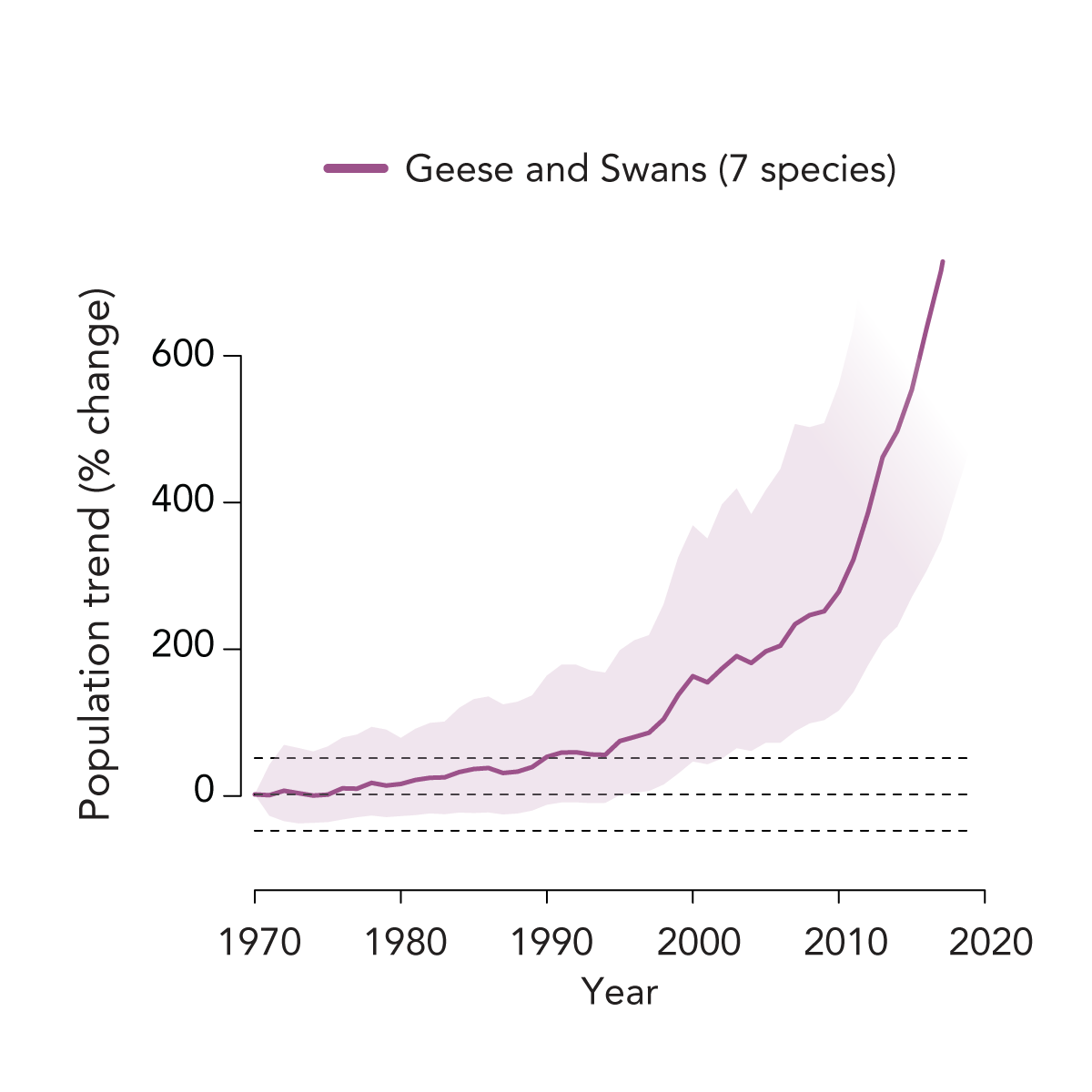

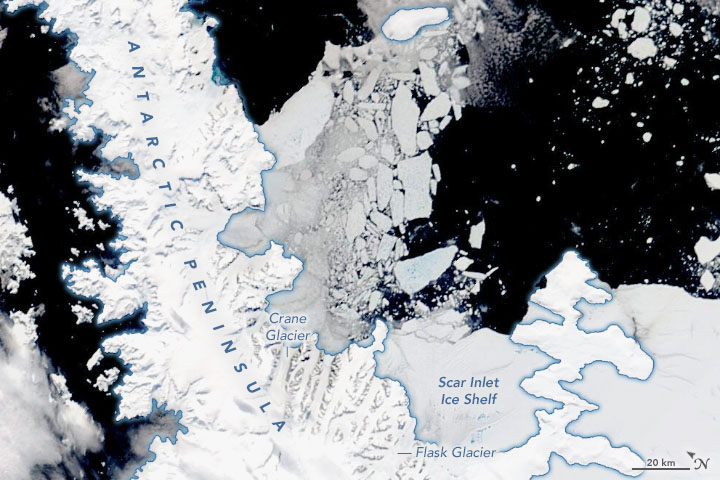

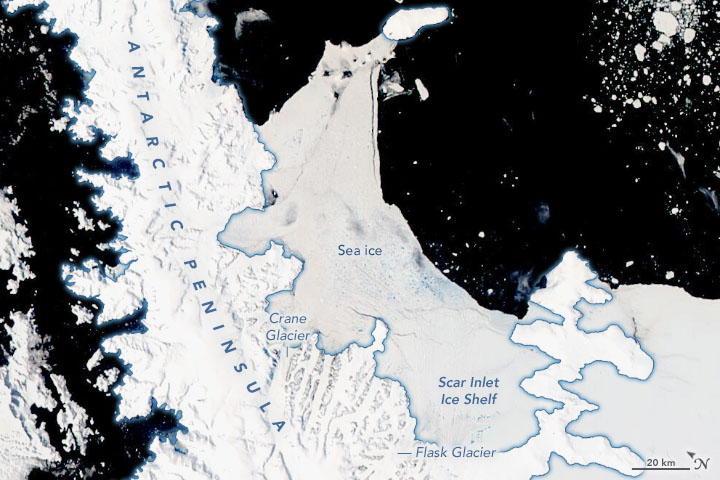

One worrying part is that the sea ice is shrinking, which releases glaciers to slide faster to the ocean. When the ice from glaciers hits the ocean, it breaks off and eventually melts—raising sea level (and also altering salinity, warming the ocean, and other changes). This process feeds back, further warming and speeding melting.

The question is whether there is a tipping point, after which the melting accelerates irreversibly. And if so, have we already crossed it?

The good news is that this is all geology. Even if Antarctica crashes, going into irreversible rapid melt down, it will take decades.

The bad news is that we still have a lot of missing data for this part of the world. Pretty much every study finds surprising things, most of them alarming. Rapidly retreating grounding lines. Huge underground canyons under the ice, filling with warming sea water. Giant lakes under the ice. Who knows what awaits discovery?

There are a number of expeditions in progress which will return a lot more data about the ice and oceans in East Antarctica. I expect there will be surprises, and most of them will not be good news.

- Alec Luhn, Why East Antarctica is a ‘sleeping giant’ of sea level rise, in BBC Future, March 12, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20230309-climate-change-the-sea-level-rise-locked-in-east-antarctica