Plant communications is one of the coolest things in contemporary biology. All animal life depends on plants, of course, but plants also turn out to have complex social systems and even intelligence of a non-human sort. It’s hard for us to understand because, compared to plants, we are “hasty” (as Tolkien so memorably put it.)

In the last twenty years, it has become clear that a forest is not a bunch of trees, but complex network more like a city. Furthermore, not only the trees, but also the microbes and fungi are part of this amazing communication and transport system.

Researchers from British Colombia have tagged this the “Wood wide web”, which is certainly catchy if not entirely apt.

This summer, an international team report on a global map of forest symbiotes, i.e., the fungal ecology under the ground of forests around the planet [2]. Different trees need different fungi, so a map of the fungi is also a map of the kinds of trees there.

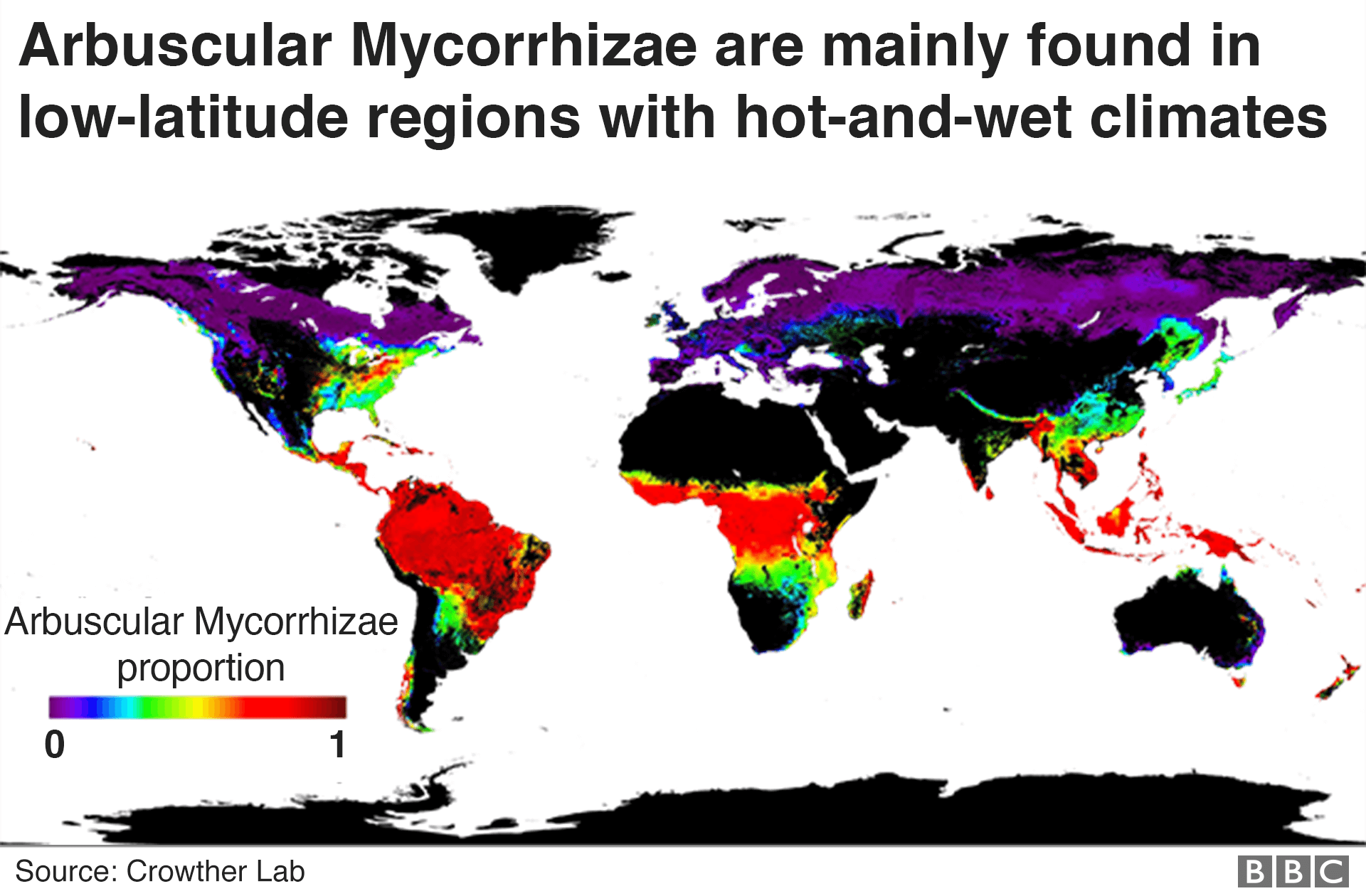

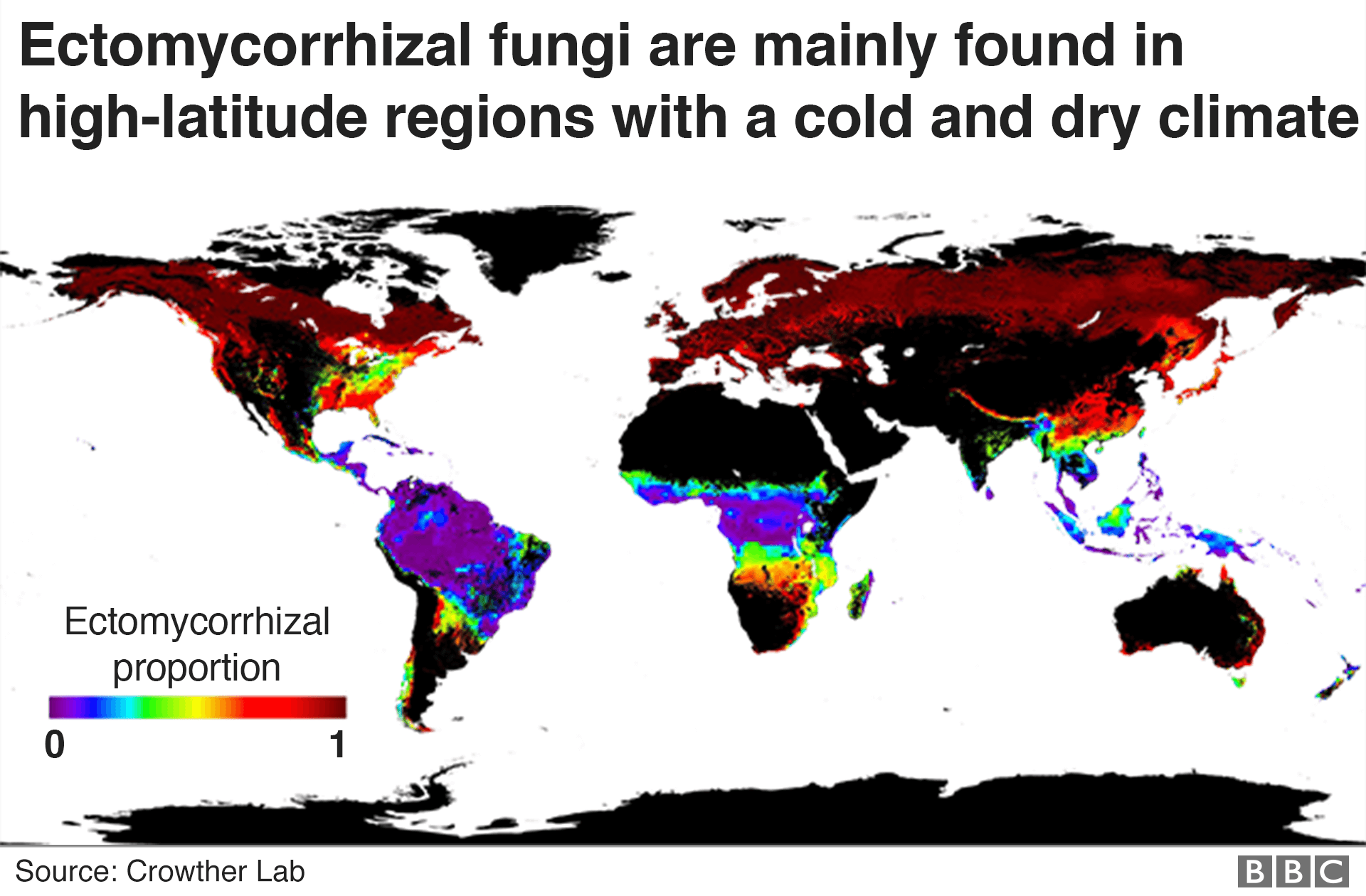

The study finds that there are two major types of microbial symbionts (and therefore, trees), ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal. The two different types appear adapted to different climactic conditions. (Actually they found five important classes, but the top two predominate.)

[Caveat: my grasp of these microbial species is limited, so some of my coments may be confused or confusing. Please refer to the paper for a full and correct explanation of the findings.]

Ectomycorrhizal trees live in dry high latitudes (places with winter), where decomposition is inhibited in some seasons. arbuscular mycorrhizal trees live in warm wet a seasonal areas (tropics), where decomposition is continuous. This is visible in the rather clear geographic delineation of areas on the map: the climate drives the microbes, which determine which trees will thrive where.

Underlying this all is the relationship between the microbial world and trees. The underground microbes deliver nutrients to the forest, and in exchange, trees deliver sugar (a lot of Carbon!) and other products of photosynthesis to the microbes. Ectomycorrhizal fungi decompose leaf litter and other materisal deliver Phosphorous and Nitrogen from soils to trees. Arbuscular mycorrhizal transport Phosphorous from minerals (not depending on decomposition).

Using data from the Global Forest Biodiversity Initiative database, to assemble a map of the types of trees from 1 million recorded locations. The research mapped these species to their known microbial symbiotes, to infer a map of the symbiotes. The symbiotes were classified into five main groups, which they term “tree symbiotic guilds”.

This dataset was used to investigate correlations of climate soil, topography, estimated decomposition rates, and other variables with these guilds. The data suggest that there is a positive feedback between climate and decomposition, which cause sharp transitions in the cost benefits and efficiency of the different symbiotes.

“The abrupt transitions that we detected between forest symbiotic states along environmental gradients suggest that positive feedback effects may exist between climatic and biological controls of decomposition” ([2], p. 408)

One implication of this hypothesis is that relatively small, gradual changes in climate will lead to rapid changes in the symbiotes and the trees above. They report simulations of future climate (circa 2070) which predict that the relatively small climate change could result in a 10% decline of ectomycorrhizal trees, which will be replaced with others.

However, the study suggests the close links between the atmosphere, soil, and plant life.

“our finding that climatic controls of decom- position are the best predictors of dominant mycorrhizal associations provides a mechanistic link between symbiont physiology and climatic controls on the release of soil nutrients from leaf litter.” ([2], p. 407)

This hypothesized turnover is potentially important because the ectomycorrhizal fungi are prodigious collectors of Carbon, while arbuscular mycorrhizal release Carbon into the atmosphere. A large change over from the former to the latter would mean that less CO2 would be equestered by the forests, further accelerating changes to the atmosphere through a positive feedback.

- Claire Marshall, Wood wide web: Trees’ social networks are mapped, in BBC News – Science & Environment. 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-48257315

- B. S. Steidinger, T. W. Crowther, J. Liang, M. E. Van Nuland, G. D. A. Werner, P. B. Reich, G. Nabuurs, S. de-Miguel, M. Zhou, N. Picard, B. Herault, X. Zhao, C. Zhang, D. Routh, K. G. Peay, Meinrad Abegg, C. Yves Adou Yao, Giorgio Alberti, Angelica Almeyda Zambrano, Esteban Alvarez-Davila, Patricia Alvarez-Loayza, Luciana F. Alves, Christian Ammer, Clara Antón-Fernández, Alejandro Araujo-Murakami, Luzmila Arroyo, Valerio Avitabile, Gerardo Aymard, Timothy Baker, Radomir Bałazy, Olaf Banki, Jorcely Barroso, Meredith Bastian, Jean-Francois Bastin, Luca Birigazzi, Philippe Birnbaum, Robert Bitariho, Pascal Boeckx, Frans Bongers, Olivier Bouriaud, Pedro H S Brancalion, Susanne Brandl, Francis Q. Brearley, Roel Brienen, Eben Broadbent, Helge Bruelheide, Filippo Bussotti, Roberto Cazzolla Gatti, Ricardo Cesar, Goran Cesljar, Robin Chazdon, Han Y. H. Chen, Chelsea Chisholm, Emil Cienciala, Connie J. Clark, David Clark, Gabriel Colletta, Richard Condit, David Coomes, Fernando Cornejo Valverde, Jose J. Corral-Rivas, Philip Crim, Jonathan Cumming, Selvadurai Dayanandan, André L. de Gasper, Mathieu Decuyper, Géraldine Derroire, Ben DeVries, Ilija Djordjevic, Amaral Iêda, Aurélie Dourdain, Nestor Laurier Engone Obiang, Brian Enquist, Teresa Eyre, Adandé Belarmain Fandohan, Tom M. Fayle, Ted R. Feldpausch, Leena Finér, Markus Fischer, Christine Fletcher, Jonas Fridman, Lorenzo Frizzera, Javier G. P. Gamarra, Damiano Gianelle, Henry B. Glick, David Harris, Andrew Hector, Andreas Hemp, Geerten Hengeveld, John Herbohn, Martin Herold, Annika Hillers, Eurídice N. Honorio Coronado, Markus Huber, Cang Hui, Hyunkook Cho, Thomas Ibanez, Ilbin Jung, Nobuo Imai, Andrzej M. Jagodzinski, Bogdan Jaroszewicz, Vivian Johannsen, Carlos A. Joly, Tommaso Jucker, Viktor Karminov, Kuswata Kartawinata, Elizabeth Kearsley, David Kenfack, Deborah Kennard, Sebastian Kepfer-Rojas, Gunnar Keppel, Mohammed Latif Khan, Timothy Killeen, Hyun Seok Kim, Kanehiro Kitayama, Michael Köhl, Henn Korjus, Florian Kraxner, Diana Laarmann, Mait Lang, Simon Lewis, Huicui Lu, Natalia Lukina, Brian Maitner, Yadvinder Malhi, Eric Marcon, Beatriz Schwantes Marimon, Ben Hur Marimon-Junior, Andrew Robert Marshall, Emanuel Martin, Olga Martynenko, Jorge A. Meave, Omar Melo-Cruz, Casimiro Mendoza, Cory Merow, Abel Monteagudo Mendoza, Vanessa Moreno, Sharif A. Mukul, Philip Mundhenk, Maria G. Nava-Miranda, David Neill, Victor Neldner, Radovan Nevenic, Michael Ngugi, Pascal Niklaus, Jacek Oleksyn, Petr Ontikov, Edgar Ortiz-Malavasi, Yude Pan, Alain Paquette, Alexander Parada-Gutierrez, Elena Parfenova, Minjee Park, Marc Parren, Narayanaswamy Parthasarathy, Pablo L. Peri, Sebastian Pfautsch, Oliver Phillips, Maria Teresa Piedade, Daniel Piotto, Nigel C. A. Pitman, Irina Polo, Lourens Poorter, Axel Dalberg Poulsen, John R. Poulsen, Hans Pretzsch, Freddy Ramirez Arevalo, Zorayda Restrepo-Correa, Mirco Rodeghiero, Samir Rolim, Anand Roopsind, Francesco Rovero, Ervan Rutishauser, Purabi Saikia, Philippe Saner, Peter Schall, Mart-Jan Schelhaas, Dmitry Schepaschenko, Michael Scherer-Lorenzen, Bernhard Schmid, Jochen Schöngart, Eric Searle, Vladimír Seben, Josep M. Serra-Diaz, Christian Salas-Eljatib, Douglas Sheil, Anatoly Shvidenko, Javier Silva-Espejo, Marcos Silveira, James Singh, Plinio Sist, Ferry Slik, Bonaventure Sonké, Alexandre F. Souza, Krzysztof Stereńczak, Jens-Christian Svenning, Miroslav Svoboda, Natalia Targhetta, Nadja Tchebakova, Hans ter Steege, Raquel Thomas, Elena Tikhonova, Peter Umunay, Vladimir Usoltsev, Fernando Valladares, Fons van der Plas, Tran Van Do, Rodolfo Vasquez Martinez, Hans Verbeeck, Helder Viana, Simone Vieira, Klaus von Gadow, Hua-Feng Wang, James Watson, Bertil Westerlund, Susan Wiser, Florian Wittmann, Verginia Wortel, Roderick Zagt, Tomasz Zawila-Niedzwiecki, Zhi-Xin Zhu, Irie Casimir Zo-Bi and Gfbi consortium, Climatic controls of decomposition drive the global biogeography of forest-tree symbioses. Nature, 569 (7756):404-408, 2019/05/01 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1128-0